by Meru S.

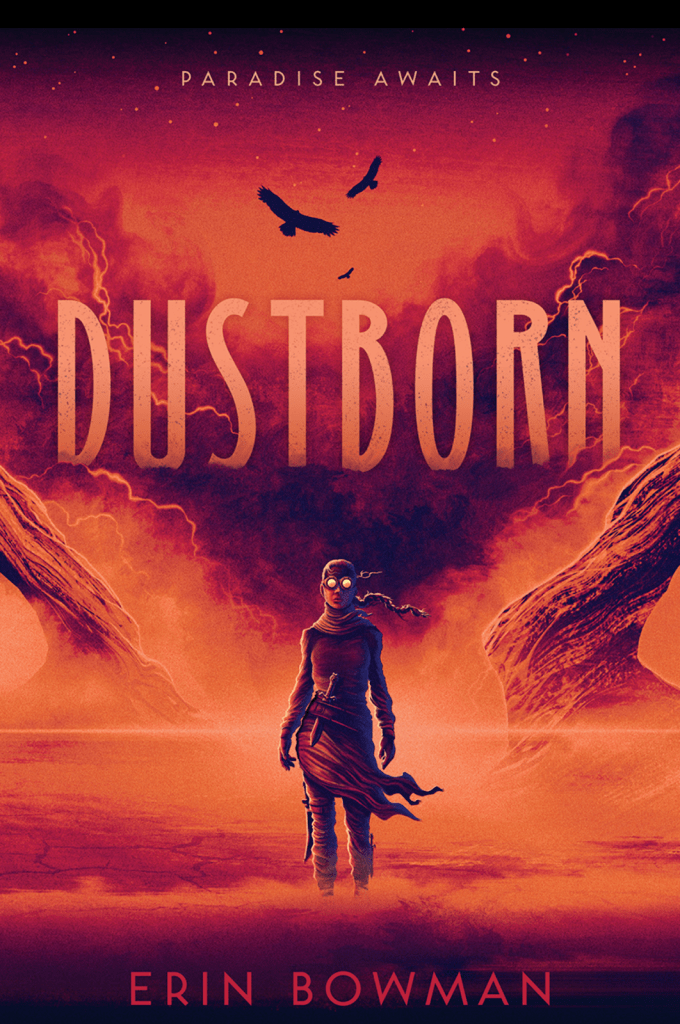

Far across the desolate sands lies the Verdant, rumored to be a lush land filled with what the Wastes’ deserts lack. And the only map to this idyll is branded onto the backs of Delta and her friend Asher, who has been missing for years. Delta must keep her back concealed, as many in the Wastes would go to any lengths for the map. Her life is already arduous, but when her mother and fellow villagers are captured in a raid during a storm, and her village burned to cinders, she must undertake the perilous journey across the Wastes to find her family.

In Erin Bowman’s captivating and thrilling novel, Dustborn, Delta braves travails only to find that she can trust nearly none in the Waste. Daring escapes lead to the unveiling of mysteries—the most unforeseen of them all hidden at the Verdant.

Published in 2021 by Clarion Books, Dustborn has been recognized as a Young Adult Library Services Association (YALSA) “2022 Best Fiction for Young Adults title,” a New York Public Library “2021 Best Teen Books” title, and is a 2022 Bank Street selection for “Best Children’s Books of the Year.”

Kirkus Reviews has commended the novel as “intense, gritty, and propulsive . . . Will keep readers turning the pages,” and the Publishers Weekly praises the plot as “absorbing world-building [that] propels this fast-paced adventure.”

A perfect read for enthusiasts of The Hunger Games, Dustborn follows a post-apocalyptic and dystopian plot. Delta’s initial callous temperament evolves into caring determination; her character arc will, no doubt, have readers cheering her on, wishing her success on a journey that will tickle your funny bone and set your heart beating. Erin Bowman wields her words to seamlessly weld together action, romance, loss, and adventure, forging a tale that will leave bibliophiles eager to peruse its pages yet again.

Dustborn is available at Barnes and Nobles, Indie Bound, and on Amazon.

Erin Bowman is a New Hampshire-based author. Her teen and young adult fiction includes the Contagion duology, the Taken trilogy, the Vengeance series, The Girl and the Witches Garden, and In the Dead of Night. Additionally, she has contributed to an historical anthology titled Radical Elements, which features tales of young women who stood up against society’s will. Visit her website at embowman.com.